Exactly thirty years ago – on December 16th, 1980 – the Monument to the Fallen Shipyard Workers was revealed in Gdańsk, as a consequence of the negotiations between the Polish Communist government and the Solidarity movement. The present year has marked the 30th anniversary of the Solidarity, and two months ago, I participated in an international conference in Wrocław, organized by the Polish Institute of National Remembrance as one part of this commemoration. The theme of the conference was the international reaction to the Polish Solidarity movement and the ensuing crisis. Since I happen to be a Finn, my own presentation dealt with the Finnish attitudes towards the Polish situation in the 1980s.

An important thing to remember is that while the emergence of the Solidarity movement in Poland generated widespread enthusiasm in Western Europe and Scandinavia, Finland was placed in a more difficult position. Although Finland was a member in good standing in the Nordic Council and an associated member in the EFTA, the foreign policy of the country was still guided by the necessity to maintain orderly relations with the USSR. The cornerstone of this foreign policy was the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, signed between Finland and the USSR in 1948. During the subsequent presidencies of J. K. Paasikivi and Urho Kekkonen, the treaty had assumed quasi-canonical status in the bilateral relations between Helsinki and the Kremlin, and this status quo continued also during the presidency of Mauno Koivisto in the 1980s.

These “special relations” between the two neighboring states did not translate in direct Finnish subservience to the USSR. Indeed, president Kekkonen proved to be ready to resist the most unwelcome encroachments, as testified by the well-orchestrated expulsion of the Soviet ambassador Alexis Belyakov from Helsinki in 1971 and the regular refusals to the Soviet suggestions of military cooperation. Meanwhile, covert exchange of military intelligence was taking place between the Finnish Defence Forces and the United States. However, the official Finnish tendency to avoid all public actions which would be likely to antagonize the Soviets was regularly demonstrated in passive self-censorship as well as in the willingness of the aspiring politicians to intrigue with the resident Soviet officials. This tendency had arguably reached its peak in the 1970s, and had an effect also on the formal attitudes towards the Polish Solidarity movement in the early 1980s.

The rise of the Solidarity movement coincided with a period of power transition in Finland. The ailing president Kekkonen had made his last visit to Moscow in November 1980, and a month later, he experienced a severe stroke. During the winter of 1980-1981, Kekkonen seriously considered retiring from his post as the head of state, which he eventually did in October 1981. The temporary presidential authority was transferred to the Social Democratic Prime Minister Mauno Koivisto, and the election spring of 1982 was dominated by an intense campaigning, which Koivisto eventually won. During this time, the situation in Poland had escalated from the first early strikes – which had shadowed also Kekkonen’s state visit to the USSR – to the government crackdown and the martial law.

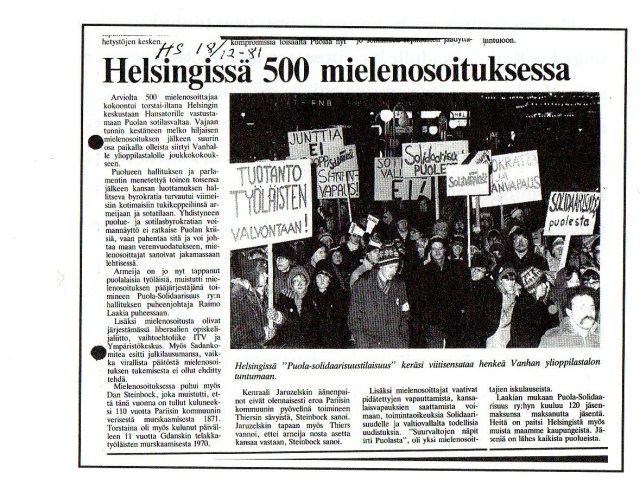

The developments in Poland did spark off a very small-scale grass-roots movement also in Finland. At the centre of these events was Raimo Laakia, a left-wing journalist and a citizen activist. This largely Helsinki-based pro-Solidarity movement drew its support from several small splinter groups; former Maoists, anarchists, the nascent Finnish “Green” movement and also the new generation of teenage peace activists, who opposed not only the American missile plans in Western Europe, but also the Soviet militarism. Already in March 28th 1981, a day after the largest Polish strike so far, Laakia and his activists were able to orchestrate a demonstration of four hundred people in Helsinki. After the enactment of the martial law, Laakia’s group organized another demonstration on a similar scale in December 18th, portrayed in the newspaper article above. The title of the article reads: “Five hundred in a demonstration in Helsinki”, and the placards in the photograph include slogans such as “Production in the Supervision of the Workers!”, “Democracy and the Freedom of Speech!” and “On behalf of the Solidarity!”.

The developments in Poland did spark off a very small-scale grass-roots movement also in Finland. At the centre of these events was Raimo Laakia, a left-wing journalist and a citizen activist. This largely Helsinki-based pro-Solidarity movement drew its support from several small splinter groups; former Maoists, anarchists, the nascent Finnish “Green” movement and also the new generation of teenage peace activists, who opposed not only the American missile plans in Western Europe, but also the Soviet militarism. Already in March 28th 1981, a day after the largest Polish strike so far, Laakia and his activists were able to orchestrate a demonstration of four hundred people in Helsinki. After the enactment of the martial law, Laakia’s group organized another demonstration on a similar scale in December 18th, portrayed in the newspaper article above. The title of the article reads: “Five hundred in a demonstration in Helsinki”, and the placards in the photograph include slogans such as “Production in the Supervision of the Workers!”, “Democracy and the Freedom of Speech!” and “On behalf of the Solidarity!”.

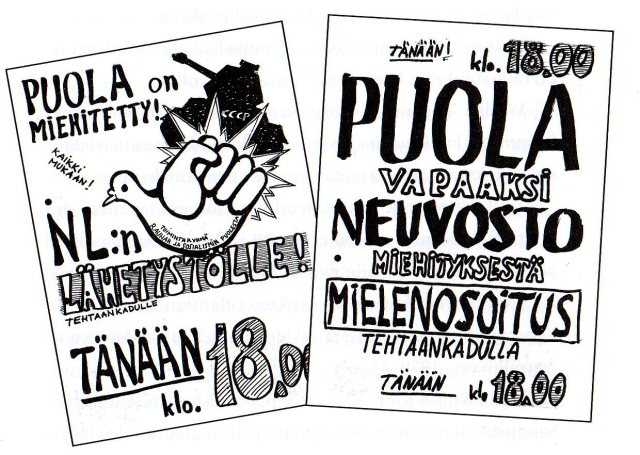

Below, there are placards which were drawn by Laakia’s group and which were supposed to be used in the case of an actual Soviet intervention. The one on the left reads “Poland is occupied! Everyone to the Soviet embassy today at 18:00!” and the one on the right states “Freedom for Poland, end the Soviet occupation! Demonstration today at the Factory Street at 18:00!”. Factory Street – in Finnish, “Tehtaankatu” – is the location of the Russian embassy in Helsinki still today.

This spontaneous Finnish pro-Solidarity movement was very much an intellectual phenomenon. The group published its news mostly through the small environmentalist newspaper “Komposti” (“Compost”), owned by Pekka Haavisto, today a notable Green politician and a potential presidential candidate in the 2012 elections. Other notable participants were Dan Steinbock, a young Finnish-Jewish economist who had gained fame by criticizing the counterculture movements and Ville Komsi, one of the first MPs of the Finnish Green movement. The significance of the Green participants in the movement resulted in a humoristic episode when Jakub Święcicki was invited from Sweden to hold a lecture in Finland. During their visit to Turku, the Finnish hosts took Święcicki for a lunch at the local vegetarian restaurant, even though he was, as a Pole, more inclined to eat meat.

(I should note that when I discussed with Święcicki in October, he did not recall this episode at the vegetarian restaurant recited in Laakia’s memoirs. The story may be apocryphical, or perhaps it took place with another activist. For example, aside from Święcicki, Anna Bogucka also visited Finland, and the members of the old Polish community in Finland, such as pianist Michał Zieliński, were also active in the pro-Solidarity movement.)

The Finnish “Solidarity for Poland”-association was eventually unable to formally register itself. Even more surprisingly, the members were covertly black-listed by the Finnish foreign ministry. Laakia received the black list by accident in November 1981, and he suspected that its original version had been drafted by a mole, a young man known simply as “the electrician”, who had been involved in the movement from April to June 1981, until his arrest by the Finnish Police on drug charges. The question of “the electrician” and his role was subsequently investigated by the Finnish Security Police, and Laakia himself has suspected that the man had actually operated for the Soviet embassy in Helsinki.

Since the formal registration of the association was denied, it was unable to organize any formal fundraising. The requests were revoked by the social democratic minister of interior Matti Luttinen in the Finnish Parliament on November 11th 1983, on the Polish Independence Day. Seven months before, the Finnish pro-Solidarity group had published its last official leaflet.

As mentioned, Laakia’s action group did attract following from small left-wing circles such as Maoists, but for the Finnish mainstream left-wing parties, the question of expressing open support for Solidarity was difficult. Especially difficult it was for the Social Democrats, who had, after a long period of uncertainty, finally managed to establish their own “confidential relations” with President Kekkonen and the USSR during the 1970s. This achievement had secured the SDP a position where they often were able to be in charge of the government coalition, which was the case continuously from 1977 to 1987. The period from 1981-1982 was particularly crucial for the SDP, because their candidate, Prime Minister Mauno Koivisto was running for president. Koivisto had exercised the executive power already at the time of President Kekkonen’s illness, and has stated in his memoirs that the reports of the Finnish military intelligence had made him concerned of the possibility of the Soviet intervention in Poland already in the autumn of 1981. Koivisto has also stated as his belief that the martial law spared Poland from a far greater tragedy.

With their new power, the Social Democrats were entrusted also with a new responsibility to preserve the Finnish foreign policy on an even keel. Consequently, although the plight of the Polish labour movement did not fail to inspire sympathy among the Finnish Social Democrats, their official position was scepticism. Expressions of open sympathy were not considered worth the potential political repercussions. Thus, the Social Democratic newspapers generally expressed their hope that the movement would be a passing phenomenon. Perhaps the boldest statement was made by the Social Democratic newspaper “Kansan lehti” (“People’s Newspaper”) from Tampere, which openly stated that the wide support enjoyed by the Solidarity and its genuine role as a labour movement were signs of serious discontent and structural weaknesses within People’s Democracies. The declaration of the martial law was mostly regarded as an unavoidable outcome by the Finnish Social Democratic press, although the newspapers did also criticize the curtailment of civil rights in Poland.

The most open Social Democratic action was taken by Tarja Halonen, at the time a Social Democratic MP, a trade union lawyer and today the President of the Republic. Halonen was one of those members of the parliament who attempted to initiate a formal inquiry demanding an investigation on the public refusal to allow the official registration of Laakia’s pro-Solidarity-association. However, these initiatives were by no means comparable to the reactions which the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 or the Chilean military coup in 1973 had provoked within the Finnish left-wing parties.

The reaction of the Finnish trade unions was even more ambiguous. With the declaration of the martial law in Poland, the Finnish Central Organization of the Trade Unions (SAK) joined the Council of Nordic Trade Unions in the condemnation of general Jaruzelski’s actions. The decision provoked an instant rebuke from the Finnish foreign ministry, which accused the SAK for jeopardizing the Finnish relations with the USSR. By 1986, the chairman of the SAK, Pertti Viinanen, had learned his lesson, and criticized the decision of the ICFTU to accept the Solidarity membership. The Finnish SAK also maintained contacts with the Polish OPZZ, the official labour union organization set up by Jaruzelski’s government. Simultaneously, the SAK tried to walk a tightrope and organized humanitarian assistance for Polish workers, together with the Finnish Red Cross. Compared to the simultaneous Swedish assistance for the Solidarity, however, these Finnish actions were minimal.

While the Finnish Social Democrats and trade unions were at least partly obligated to express sympathy towards the Solidarity but also required to remain cautious, the Finnish Communists were in a somewhat different situation. The Finnish Communist Party (SKP) operated in the parliamentary politics through an umbrella organization named Finnish People’s Democratic Alliance (SKDL). The ranks of the SKDL were by no means solid, and the alliance included also “revisionist” left-wing socialists, who were not members of the Communist Party. The most notable of them was Ele Alenius, a long-time SKDL prime secretary, and a respected socialist theoretician who was often suspected of “anti-Soviet tendencies”. Alenius, who had authored a book titled “Socialist Finland”, advocating a democratic transition to socialism and describing Yugoslavia as a possible alternative to the Soviet model, was the only high-profile politician who signed the address on behalf of the Solidarity, and openly supported the Polish labour movement. Among other left-wing socialist signatories was also Ilkka-Christian Björklund, who was a member in the SKDL parliamentary group in 1972-1982 and afterwards the General Secretary of the Nordic Council in 1982-1987.

Ever since the 1960s, the Finnish Communist movement had also split between the mainstream eurocommunists of Aarne Saarinen and the orthodox Marxist-Leninist opposition of Taisto Sinisalo. The majority Communists were, by and large, inclined to support the principle that every country should be allowed to find its own way towards socialism, but they also regarded the actions of the Solidarity as an “obstacle for the reforms in Poland”. Likewise, the declaration of martial law was considered as a tragic, but unavoidable situation. The hard-line Finnish minority communists, who still wielded a considerable influence among certain sectors of the university students, were not restrained by such shackles of political correctness. Starting from 1980, the main newspaper of the minority communists, “Tiedonantaja” (“Information”), mounted a systematic attack against the Solidarity movement as a “counterrevolutionary non-socialist movement”. The minority communists also organized “class-conscious” demonstrations against the Solidarity movement at the Polish embassy, and occasionally confronted Laakia’s activists on the streets of Helsinki, usually in a very ridiculous fashion.

While the Finnish Social Democrats and Communists had their own reasons for mixed feelings or open reluctance towards the Polish Solidarity movement, the Finnish centrist and right-wing commentators retained a harsh attitude based on supposed realpolitik. Columnist Olli Kivinen, today a notable right-wing champion of the NATO alliance in Finland, issued a favourable comment on Jaruzelski’s actions on the day after the declaration of the martial law. Kivinen stated that “the Solidarity had become drunk with power, and was using this power irresponsibly”, and that the impending “hunger winter” and the “too drastic changes” had created a situation where “even a leader as liberal and pragmatic as Jaruzelski could no longer remain passive”. Harri Holkeri, the presidential candidate of the right-wing National Coalition party, also stated openly after seeing “Solidarity” pin badges distributed by Laakia’s group that he “would not wear those, because it’s an intrusion in the internal affairs of another country”. At least one person, Juha Siikavuo, was actually discharged from the youth organization of the National Coalition, because he suggested that the party should support the Solidarity.

The reason for this reluctance of the largest Finnish right-wing party was the fact that in spite of its good record in the elections – over 20% in 1979 – it had remained in opposition ever since 1966, mostly as a punishment of its critical attitude towards President Kekkonen as well as for foreign political reasons. By the early 1980s, the new National Coalition leadership was determined to restore the position of the party in the future government coalitions. Consequently, anything which could be construed as a criticism of the USSR was, by necessity, out of the question.

The leading politicians of the Centre Party, which had always held the balance of power in the Finnish politics as well as enjoyed the goodwill of Moscow, had no reason to change their opinions. The Centrist foreign minister Paavo Väyrynen – also a minister in the present cabinet in 2010 – and the Speaker of the Parliament Johannes Virolainen – who was also the President of the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) at the time – made official state visits to Warsaw and met general Jaruzelski. All in all, these Finnish reactions to the Polish crisis provided a painful and perhaps the most evident demonstration of the so-called “finlandization”, which placed Finland in a category of its own among the democratic European countries during the Cold War era.

The only support for Solidarity from the Finnish non-socialist political sector came from the very small “Constitutional Right-Wing Party” founded by the recently-deceased Georg C. Ehrnrooth – an openly pro-Western, anti-Communist and anti-Soviet party which had emerged as a protest movement against President Kekkonen and had a representation of one, sometimes two MPs in the Finnish Parliament in 1973-1979 and 1983-1987. Panu Toivonen, the secretary of the Party, was involved in the activities of Laakia’s group, where he made a curious hard-line right-wing addition to the mixed company of the Greens, anarchists, Maoists and revisionist left-wing socialists. Later in the 1980s, the Constitutional Right-Wing Party also invited Afghan fighters to its party convention.

A peculiar role in the official Finnish position towards the Solidarity movement was also played by the mysterious Finnish informant of the East German intelligence service (Stasi). This person, code-named “Steffen” or “XV/772/68” relayed confidential information and reports from the Finnish embassy in Warsaw to the East Germans. The identity of this person remains unknown, but the former advisor to President Martti Ahtisaari, Alpo Rusi – who himself has been suspected and officially cleared of Stasi contacts – has made the assumption that “Steffen” was Taneli Kekkonen, the son of President Kekkonen, who served as the Finnish ambassador to Warsaw in 1980-1984 and was accidentally arrested by the Polish police for a brief time during the martial law.

At the time when the Solidarity movement was gaining momentum and Poland ended up under the martial law, the Finnish political establishment was undergoing a volatile period of power transition after President Kekkonen’s resignation. In this particularly uncertain period, the Finnish government was wedded to its time-honoured principles in foreign policy and consequently reluctant to irritate the USSR in any way. As a result, most of the leading politicians remained sceptical, indifferent or hostile towards the Polish Solidarity movement. For Finland as a whole, the Polish crisis was one of those moments in the Cold War when the country had no choice but to cling on to her neutrality, avoid any grand gestures and safeguard its own interests, much as during the Berlin crisis of 1962 or the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. The declaration of the martial law and the absence of the Soviet intervention undoubtedly came as a relief to the Finnish political leadership. With the USSR still an undisputed superpower, no one was yet mentally prepared for the same international upheavals which materialized ten years later, and no one was ready to hope for the best.

Meanwhile, the few expressions of open support for Poland emerged mostly from a few citizen activists of the younger generation, often from surprising directions. For many who were involved, this activity was part of their formative period in politics, and an important experience. For example, for the Finnish Green movement – which today enjoys a position in the government coalition – the participation in the pro-Solidarity activities was one of the first campaigns where the activists of the movement had to formulate an opinion on the international politics. More importantly, the public actions organized by Laakia’s group demonstrated that even though the political elite may have been cautious and paralyzed, a willingness to take action definitely existed within the general population.

What about the Rural Party (SMP)?

That’s a good question, and one that I hadn’t thought about. Kimmo Kivelä, who was the deputy secretary of the Youth Organization of SMP, was among the signatories of the pro-Solidarity address.

On the other hand, the list of the MPs who joined in the parliamentary inquiry demanding an explanation for the black-listing of Laakia’s action group didn’t include one single SMP representative (they had seven MPs at the time, and seventeen after 1983). I haven’t checked what comments the newspaper “Suomen Uutiset” (“Finland’s News”, the official newspaper of SMP) made on the Polish crisis, so I can’t really comment any more extensively right now. But I could check out, and, as Sarah Palin said, I’ll get back to ya.

The title of Laakia’s memorial publication – which is basically a collection of essays – is “Solidarnoscin nousu tuhosi imperiumin – Suomalaisen tukiliikkeen pieni historia” (“The rise of Solidarnosc destroyed an Empire – A small history of the Finnish support group”). Edited by Raimo Laakia himself, self-published, printed at the Gummerus press in Jyväskylä in 2005. There are two copies at the Tampere City Library.

Best,

J. J.

Pingback: Puola-solidaarisuus, Laakia ja me – Tarinamme

Pingback: Puola-solidaarisuus, Laakia ja me – Tarinamme